- About Us

- Advertise / Support

- Editorial Board

- Contact Us

- CancerNetwork.com

- TargetedOnc.com

- OncLive.com

- OncNursingNews.com

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy

- Do Not Sell My Information

- Washington My Health My Data

© 2025 MJH Life Sciences™ and CURE - Oncology & Cancer News for Patients & Caregivers. All rights reserved.

Driving Treatment Decisions and Predicting Long-Term Outcomes in Multiple Myeloma

Darlene Dobkowski, Managing Editor for CURE® magazine, has been with the team since October 2020 and has covered health care in other specialties before joining MJH Life Sciences. She graduated from Emerson College with a Master’s degree in print and multimedia journalism. In her free time, she enjoys buying stuff she doesn’t need from flea markets, taking her dog everywhere and scoffing at decaf.

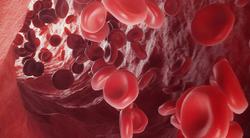

Treating multiple myeloma to minimize the amount of residual disease in the body is an ultimate goal, which can be achieved through initial therapy and maintenance therapy.

After completing initial combination therapy for multiple myeloma, maintenance therapy can help a patient maintain a response to therapy and potentially achieve minimal residual disease negativity, which is a key to a functional cure for the disease, an expert said.

In addition, testing for minimal residual disease in patients with multiple myeloma may help drive treatment decisions and lead to a more tailored approach, said Dr. Dickran Kazandjian, a professor of medicine at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center/University of Miami in Florida, at the CURE® Educated Patient® Multiple Myeloma Summit.

CURE® also spoke with Kazandjian to learn more about the importance of learning about maintenance therapy, novel therapies on the horizon and why aiming to achieve minimal residual disease negativity may improve long-term outcomes.

CURE®: Why do you think it’s important for patients to know about that topic?

Kazandjian: It's really important because some patients, after their initial diagnosis and initiation of treatment, may do really well. When they do really well — usually after the initial combination therapy — we put patients on a maintenance therapy, which resembles a lot of other chronic diseases like hypertension. Lenalidomide (Revlimid), which is the mainstream drug we use for maintenance therapy, is a pill, so it becomes very convenient.

In patients who were maybe four or five years out from initiation of maintenance, the question arises, ‘Well, there's no sign of myeloma all this time. Do I really need to continue taking this pill?’ I think it's a very difficult question to answer. Up front, patients, for the most part, don't realize and get surprised when I tell them after the initial combination therapy, likely they'll need a maintenance strategy indefinitely. When they ask me how long, it doesn't sound too good as the standard answer is “indefinitely.” It's important for patients to understand why we do it. I think the evidence behind giving (Revlimid) maintenance therapy, for example, is one of the strongest, where it not only helps patients from not progressing any further, but it also was associated with a survival benefit in a number of earlier trials. However, these trials looked at the entire patient population and didn’t zoom in on patients who may achieve minimal residual disease negativity.

In your presentation, you talked about some novel therapies. Which ones do you think have the most promise in this area?

The quadruplet-based therapies that are basically taking the lead over our triplet therapies. But not all quadruplets are the same. When you use a really well-established triplet backbone for a newly diagnosed (patient), at least in the United States, and add a highly effective fourth drug for myeloma, those are the quadruplets that patients need to be thinking about.

That's a bit abstract, but more specifically, patients really need … to receive a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory drug upfront and add on top of that … an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. Most of the studies have been with Darzalex (daratumumab), which is totally accessible. I think (Darzalex) has a lot of data to support itself in myeloma. (In addition), the company has worked on refining it, so we don't do any more weight-based dosing; it's a fixed dose for all patients. (Also, now) patients can receive it subcutaneously.

The other thing that has changed a lot is the risk of infusion reactions, which was the major issue with (Darzalex), and now we're all well versed in giving prophylactic anti-reaction medications. Subcutaneous (delivery) itself decreases the incidence of infusion reactions.

That’s not the only anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. Sarclisa (isatuximab) is another one that is catching up. And so that's another one to keep your eye on, along with a couple other less-common ones that are earlier in drug development.

Can you explain what is minimal residual disease negativity?

Minimal residual disease negativity means different things in different disease settings. In multiple myeloma, minimal residual disease — we call it MRD for short — negativity is based on the bone marrow tissue. Traditionally, when we follow multiple myeloma for how the patient is doing while on therapy, either in terms of response or, on the other end, progression, we look at it usually from the blood. We’re lucky, we have a pretty good blood surrogate (m-protein and serum free light chains), where a lot of other tumors don't. Even lymphoma, which is a close cousin, you really have to do imaging.

But we're fortunate enough to have a blood-based test to gauge response. That response only goes so far; it’s a concept where the deeper you look, the more you may be able to find. If you don’t find (any affected cells), then that gives you a deeper response (to therapy). What that is in myeloma is, your blood doesn't show anymore monoclonal protein or serum-free light chains, which are surrogate markers for myeloma, and on bone marrow biopsy, traditionally, we look at how many plasma cells and if they're monotypic or not.

What's really important for patients to know not all MRD is the same. To be able to say you’re MRD negative, you have to know what the sensitivity or the level of the detection of the test is. And so in myeloma, that means that you need your test to be able to prove that after looking at 100,000 normal cells, that not one of them is abnormal. So our current test for MRD is flow cytometry, which gives us that type of sensitivity. We also have next-generation sequencing platforms, which is not necessarily a replacement, but it’s complimentary in some cases. And that has been quoted to give a sensitivity of one in a million to be able to detect that much. But these are general averages, and each patient sample technically has its own level of detection sensitivity. That is what's gaining momentum.

This is not necessarily a new test now. We were talking about it five or 10 years ago. It’s now slowly getting incorporated. What the key is for patients to know is that at least the next-generation sequencing test … done by Adaptive Biotechnologies is FDA cleared. What that means is CMS and other payers are more likely to cover the costs, which, you can imagine, is probably fairly expensive. That's the way to go.

On the other end is, what do you do with that information? I can tell you all my patients want to know if they're MRD negative or not, the ones that Googled it and figured out MRD. It's something you want to attain.

In a lot of cases, if you don’t reach MRD negativity, we don't necessarily know what actions we could take. For example, does that mean we need to change therapy? Maybe we run the same therapy longer? Just to give a simple example, if someone has newly diagnosed myeloma, we started him on (Velcade, Revlimid and dexamethasone) or (Darzalex, Kyprolis, lenalidomide and dexamethasone), the common practice to treatments for newly diagnosed myeloma. And after two cycles, if you did a bone marrow biopsy, and the patient wasn't MRD negative, I don't know what that would mean, meaning you could easily give four to six more cycles and they may convert at that point. In fact, it’s more the exception than the rule, but it happens where I've had patients convert to MRD negativity while actually on maintenance therapy, meaning after the initial three-drug combination.

What advice would you give patients and their caregivers?

I think my biggest advice is a lot of these topics are very complicated. I spent many years focused on this. The most Important thing for patients is to be able to find a doctor that they trust, a myeloma expert, and have them walk the journey together. … And I think there's different levels of understanding. General oncologists may understand it, but it's really not the same level. And even though it’s the second most common blood cancer, blood cancers are rare. So it really behooves everyone to reach out.

Out of all the negative things, at least one of the positive things with the COVID-19 pandemic is (that) it has made telemedicine more accessible. And now a lot of folks, including us here at Sylvester, are offering that to patients. So even if it's a one-time shot or a once in a while shot to get a second opinion, I think it's probably worthwhile.

This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

For more news on cancer updates, research and education, don’t forget to subscribe to CURE®’s newsletters here.

Related Content: